Speeding up the JavaScript ecosystem - Tailwind CSS

📖 tl;dr: Since its inception, Tailwind CSS has become a super popular way to style web projects. This time we will be taking a look at the architecture that powers it and what can be done to improve it.

Admittedly, I currently don’t have a bigger project written with Tailwind CSS at hand at the moment. Those that do use Tailwind are too small in scope to make a meaningful performance analysis. So I thought what better way than to profile Tailwind on its very own tailwindcss.com site! Right at the start I ran into a problem though: The project is built with Next.js which makes it very difficult to obtain meaningful traces off. What’s more is that the traces contained too much noise completely unrelated to TailwindCSS.

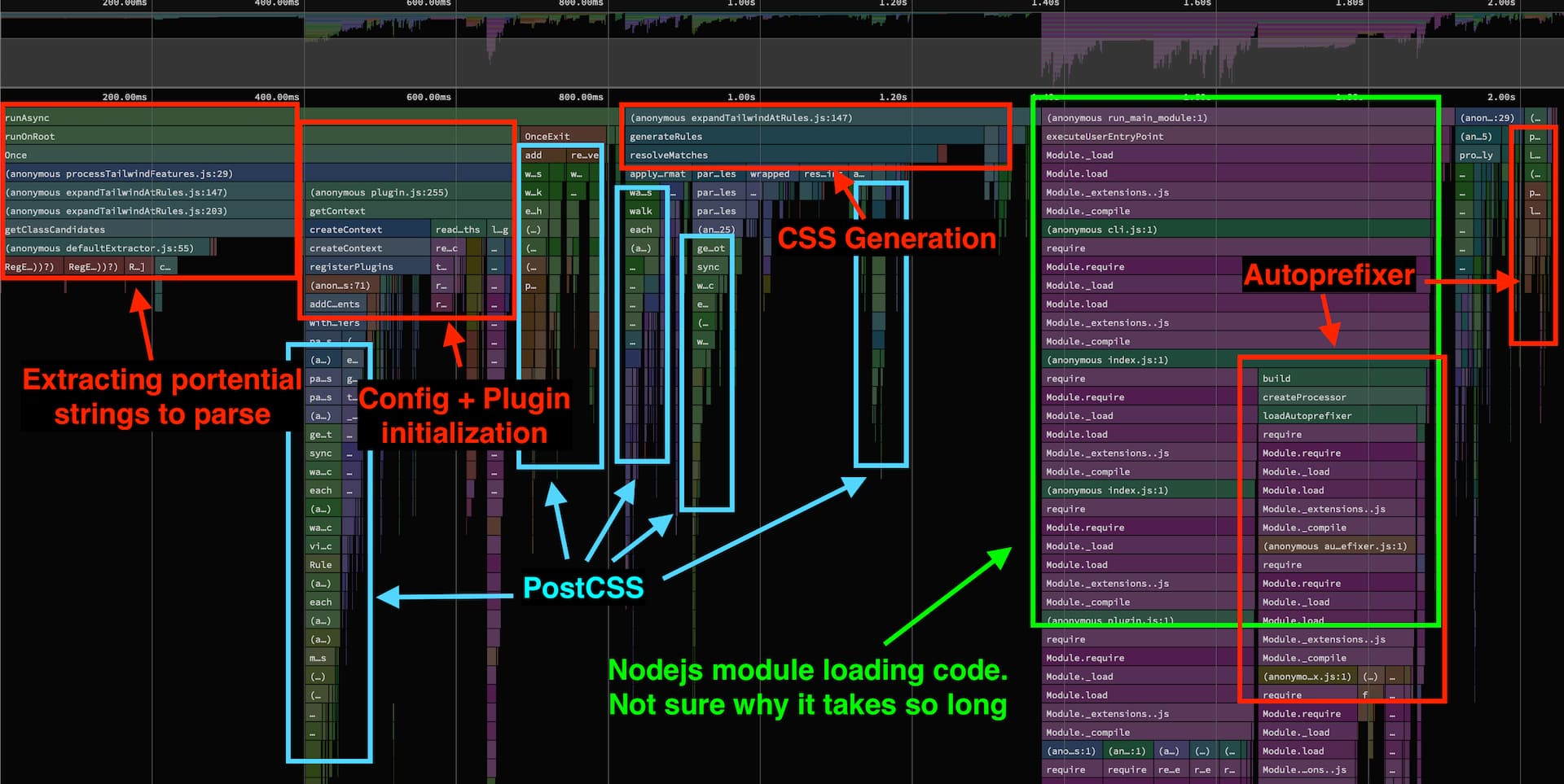

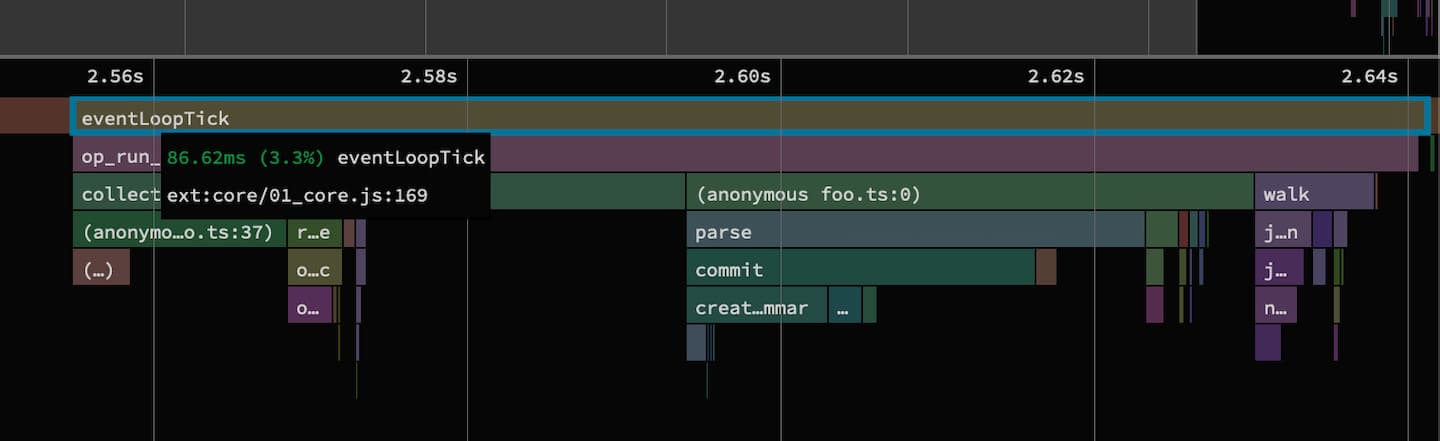

Instead, I decided to run the Tailwind CLI over the project with the very same config to obtain some performance traces. Running the CLI build takes a total of 3.2s, whereas at runtime 1.4s were spent in Tailwind. The machine the numbers are pulled from is my personal MacBook M1 Air. Looking at the profile we can make out some key areas where time is spent:

As usual in my posts, the x-axis of the flame graph doesn’t show time “when it happened” but rather the accumulated time of each call stack which are merged together here. This makes it a lot easier to see problem areas at a glance. I’m using SpeedScope to visualize the CPU profile.

There is a block that deals with extracting potential candidates for parsing, a block for config and plugin initialization, CSS generation, some PostCSS stuff and when there is PostCSS then autoprefixer typically can be mentioned in the same breath as the two are very frequently used together. It's noticeable that loading autoprefixer without doing anything seems to consume quite a bit of time already.

Switching things up

Going through the Tailwind CSS code base and looking at the profile, there definitely some places where functions could be optimized more. But if we did that we’d only get a couple of single digit percentage improvements. In the previous posts there was typically something obvious jumping out in the profiles, but what do we do here where there is no single obvious indication where time is spent?

The secret to achieving speedups of multiple factors, not just low percentages, is less about applying generic rules or habits like “Don’t create closures inside for-loops”. It’s a common misconception that if you follow all these “best practices” that your code will be fast, because the uncomfortable truth in most instances (read not all) is that it won’t matter much. What makes code truly fast is being aware of what it’s supposed to solve and then taking the shortest path to achieve that goal.

So as a challenge, I thought it would be fun to look at what the architecture of Tailwind’s code would look like, if we built it from scratch with performance in mind. Would we make different decisions? But to be able to find an optimal architecture, we need to know which problem Tailwind solves and think of the shortest path to achieve that.

Little spoiler:

How Tailwind CSS works

At its core, the way Tailwind CSS works is that you pass it some CSS files and it looks for @tailwind rules inside of them. If it encounters such a rule it will crawl the other files in your project to look for tailwind class names and inject it in place in the CSS file where the @tailwind rule was found. There are some more aspects to it, but for sake of simplicity for this article, we’ll ignore the other at-rules for now.

/* Input */

@tailwind base;

@tailwind components;

@tailwind utilities;

.foo {

color: red;

}…is transformed to:

.border {

border-width: 1px;

}

.border-2 {

border-width: 2px;

}

/* …etc */

.foo {

color: red;

}Based on that we can identify several stages in the inner workings of Tailwind CSS:

- Scan

.cssfiles for@tailwindrules - Find all files to extract tailwind class names from based on glob patterns provided by the user in the tailwind configuration

- Once those files have been found, extract potential tailwind class names

- Parse potential tailwind class names to check if they are really a tailwind class name. If they are, generate some CSS from that

- Replace the

@tailwindrule in the original css file with the generated CSS

Optimizing the extraction stage

Since there are only three valid @tailwind rule values, we can bypass the whole PostCSS parsing step by using a basic regex:

/@tailwind\s+(base|components|utilities)(?:;|$)/gm;With this regex, finding the @tailwind rules and their position in all the CSS files is essentially free, as it takes about 0.02ms. That time hardly matters compared to the full 3.2s time it took for Tailwind CSS. When it comes to finding all files based on user specified glob pattern, there isn’t much we can do that would affect the total time, as we need to reach out to the file system anyways and we’re limited by the readFile function the runtime provides us.

However, once those files are read and we need to extract potential tailwind class name candidates, there is a lot we can do. There is a problem though: How do we detect what is a tailwind class name and what is not? It might sound simple on the surface, but it’s actually not that easy. The problem is that there is no maker or any other indication that a sequence of characters is a valid tailwind class name. There can be combinations of words which have the same format as a tailwind class name, but don’t exist.

Examples of valid tailwind class names:

ml-2border-b-green-500dark:text-slate-100dark:text-slate-100/50[&:not(:focus-visible)]:focus:outline-none

Is foo-bar a valid tailwind class name? It’s not part of the default tailwind grammar, but it could’ve been added by the user. So the only real option we have here is to reduce the search space as best as we can and then feed our parser with the remaining candidates. If the parser generated some CSS, then we know that the class name was valid. If it didn’t then it wasn’t valid. This in turn means that we need to optimize our parser to bail out as quickly as possible if it detects a string value that it has no definition for.

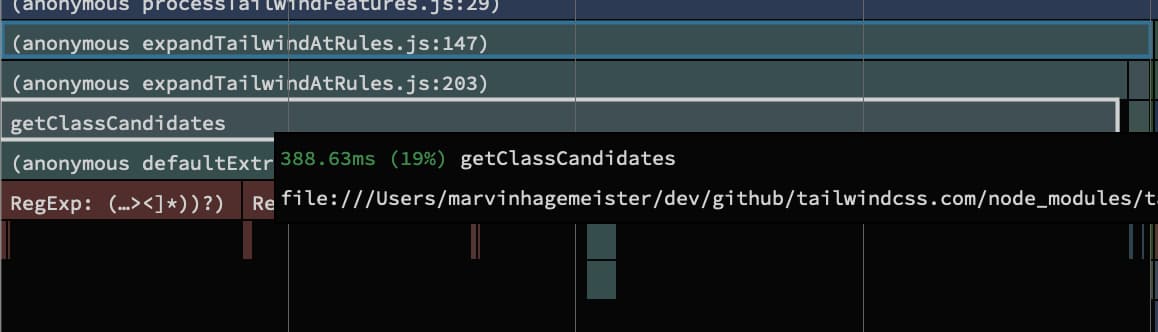

To remind ourselves: This takes about 388ms in Tailwind CSS currently.

I’ve patched Tailwind CSS locally to reveal some stats about the values the extractor pulls out.

- Parsed files: 454

- Candidate strings: 26466

But what’s much more interesting is looking at the most common top 10 values that the extraction code pulled out:

- 9774x ''

- 2634x </div>

- 1858x }

- 1692x ```

- 1065x },

- 820x ---

- 694x ```html

- 385x {

- 363x >

- 345x </p>In other words: Out of the 26466 matched strings, 19630 of them are obviously invalid tailwind class names. Now to be fair, Tailwind CSS has some caching in place to alleviate checking if something is a false positive or not. And there already is a code comment that says that any improvement to their regex could speed up Tailwind CSS by as much as 30%.

Regexing all the things

The blessing and curse at the same time of using regex here is that it isn’t language aware. It doesn’t know if we’re operating on .js or .html files and what’s worse is that languages can be embedded into each other. An .html file can host HTML, JavaScript and CSS at the same time. Same is true for JSX in .jsx files. When it comes to JavaScript code, then we can assume that we only need to look at strings.

A quick and dirty regex later, we reduced the search space from 26466 down to 9633 candidates. Still not optimal, but a lot better than what we started with. A lot of the extracted strings now resemble much more potential tailwind candidates:

relative not-prose [a:not(:first-child)>&]:mt-12nonebreak-aftergrid-template-rows- ...

Each extracted string holds one or more potential candidates. We can reduce the search space further by firing another regex on each extracted string to pull out the parts that could be a valid tailwind class name. Luckily for us, the grammar of a valid tailwind class name follows reasonably simple rules:

- No spaces allowed

- Variants must end with a colon

: - Arbitrary values are defined with wrapping brackets

[foo]. They must be located at the end of the class name - A variant can also be arbitrary:

[&>.foo]:border-2. Must still not contain spaces - Anything other than the values inside the brackets must only contain numbers, alphabetic characters or the minus sign. I’m not sure if underscore is allowed to, but I guess it could be a user defined tailwind class name

- A valid Tailwind class name must start with

[,-,!,a-zor0-9

All this matching does cost some time though and increases the total extraction time to 92ms. And after all our efforts of reducing the search space, we’re still left with around 8000 potential tailwind class names (remember, previously extracted strings could hold multiple candidates).

So far we achieved pretty commendable gains. We reduced the extraction time from Tailwind’s original 388ms down to 98ms. That’s roughly a 4x improvement.

Turning class names into CSS

At this stage we still haven’t generated any CSS rules yet. We still need some rules to replace in favor of the @tailwindcss rules in the original CSS file where we started from. But we are now in a position to do just that with the list of potential tailwind class names. A lot of these are likely false positives so we need to ensure we can bail out as quickly as possible if we detect that a class name doesn’t render CSS.

The first step is parsing the preceding variants if there are any. Remember that variants can be detected by a trailing colon : character. One key aspect of variants is that they only influence the selector and maybe the surrounding media query, if present. They are not used to generate CSS properties themselves. Parsing the variants is a bit of grunt work and nothing really special. If we detect that a supposed variant doesn’t exist we can exit early already.

What’s more interesting than variants is the rule generation aspect. The majority of tailwind class names don’t feature a variant. Since tailwind mirrors a lot of CSS properties, the amount of potential matches we need to make is quite large. I’ve tried various approaches like matching all static tailwind class names up front, putting everything in an object with methods to use like a virtual function table and more. But in the end the fastest and I felt like the easiest to maintain was one giant dumb switch statement.

function parse(lexer, config, hasNegativePrefix) {

const first = lexer.nextSegment()

switch (first) {

case “aspect”:

//...

case “block”:

if (!lexer.isEnd) return // bail out

return `display: block`

case “inline”:

if (lexer.isEnd) return `display: inline`

const second = lexer.nextSegment();

if (

second !== “block” || second !== “flex” || second !== “table”

|| second !== “grid”

) {

return // bail out

}

return `display: inline-${second}`

// ...1000 lines more of this

}

}This might look like pretty standard parser code, but there are some interesting aspects. The obvious one is that at every step we check if we’re still on a valid path. This adds a lot of additional checks, but I found that the cost for these is offset by the gains of being able to bail out earlier. In some prior iterations I made a mistake in the extracting portion and ended up feeding way too many known false positive strings to this parse function. But because the parse function quickly bails out on invalid class names it took me a while to notice as it was still fast overall.

Of note is also the hasNegativePrefix argument that’s passed to the parse() function. Many numeric based properties like padding can receive negative values by prefixing the class name with a minus - character.

"pl-2"; // -> padding-left: 0.5rem;

"-pl-2"; // -> padding-left: -0.5rem;The leading minus character is stripped before passing it to the parse() function, so that we can reuse the same case branches for both the normal and the negative case. It’s not shown here, but the parser also supports arbitrary values, the important declaration, color values with opacity and more.

Although I didn’t implement every single rule, all the syntax variations are supported. I did implement a fair share of the rules though, about 126 of them. That’s roughly 80% of the tailwind grammar. Even though this is mostly a prototype I wanted to get a better picture of how the parser would scale.

With the generated rules in hand we can now finally replace the @tailwind rule in the original CSS file. If we want it to be source map aware we can use Magic String.

With everything in place, here are the final measurements:

- Extract:

98ms - Parse:

21ms - Total time:

192ms(including runtime startup time)

The whole project consists of 5 files (excluding tests) and is just shy of 3000 lines of code.

What about Rust?

The reason our little project here is faster than the og Tailwind CSS cli is that we sidestepped parsing anything with PostCSS completely and focuses on generating CSS rules as fast as possible. The Tailwind team is currently in the process of rewriting Tailwind CSS in Rust and from what I can gather they are already far along. I don’t have any numbers for that as it’s not yet released. What remains to be solved like with any JavaScript tool that is being rewritten to rust is what their plugin story will look like. Tailwind does support custom variants or full rules being defined in their config. Once it’s out it will be interesting to compare the two.

Conclusion

This was a fun little exploration to see what the architecture of Tailwind CSS tuned for performance would look like. Admittedly, this one took me way longer to write than previous articles because of the amount of prototyping involved to arrive at something I was satisfied with. Whatever the Tailwind CSS team decides to do, I’m really looking forward to that.

To me, Tailwind CSS is the jQuery of CSS. Not everyone likes it, but the positive effect it had on the web industry is undeniable. It enables a whole new generation of developers to get into web development.

I really appreciate what they’re trying to do, because it mirrors my own path to becoming a developer. When I started with web development jQuery was at its peak and without it I would have never touched JavaScript. It wasn’t until 2 years into my career that I took an interest in JavaScript itself and learned the fundamentals. Tailwind CSS is doing exactly that for today’s developers when it comes to CSS.

I’m really glad that they exist, even if their compiler could be faster.